The idea of student empowerment over engagement is a growing conversation and trend in education. Rightly so. Many emerging ideas such as genius hour, project-based learning and others are designed to empower students. As we examine and reflect on any implementation of these ideas, we typically hear some reference to “motivated students”. If students are seen as motivated, any kind of independent learning is more likely to work. Conversely, people’s resistance to giving students more ownership and autonomy is often because they don’t feel their students are motivated.

I had a chance to visit Thames Valley School District this week in London, Ontario. I had been to the district before and seen some of the innovative work they are doing. They have a long-standing art program at one of their high schools that embodies so many of the principles of empowered learning. In addition, they recently have developed a “school within a school” concept. Essentially they are working with grade 9 teachers who were asked one question: “What if there were no subjects?” From there the district outlined the “bumpers” (must still address curricular needs, no major additional funds, must work in teams) and now nearly 20 cohorts have been formed where students are indeed driving much of their learning in a non-traditional way. I talked to many students as they were working and sharing their passion projects and it was evident they owned it. Watching the teachers be true facilitators and support and see real agency being given to students is what learning and school should be. The district’s role was to create the conditions for this to happen.

I also had the chance to chat with several teachers at lunch. As they shared their successes and challenges, I asked them “What do students need to be successful in these programs?” They talked about willingness vs motivation. Motivation suggests they have a sense of what they want to learn and just need to be let loose. While there are students who definitely fit into this category, there are far more who might not be motivated but are willing.

When you look the chart above, the motivated are the ones benefiting from empowerment. While it many might say all students should be empowered, I’d argue many aren’t ready for that yet. They don’t know what they don’t know but they would like to get there. If students or teachers are willing, I think they’re close to being motivated. The disposition of a great learner is an admission of lack of knowledge and skills, but a desire to grow them.

The teachers at Thames Valley recognized that many students, they assumed were motivated, were simply willing. They may or may not know what they’re passions were and definitely lacked the knowledge and skills to pursue them. The teachers have been working to add these skills more intentionally to their experience. The degree to which reflection was embedded for both students and teachers is what will enable their success and sustainability. The teachers were articulate and thoughtful in describing their shortcomings, needs and next steps.

After this conversation, I began to think more about the idea of being willing. The reality is, many of these types of programs exist all over the world and generally are filled with motivated students and teachers. Creating the conditions for these folks to thrive isn’t always commonplace but it really is the easy part. But creating the conditions for learners to learn and create isn’t necessarily what’s going to work for the less willing. Creating willing students and teachers is the real challenge.

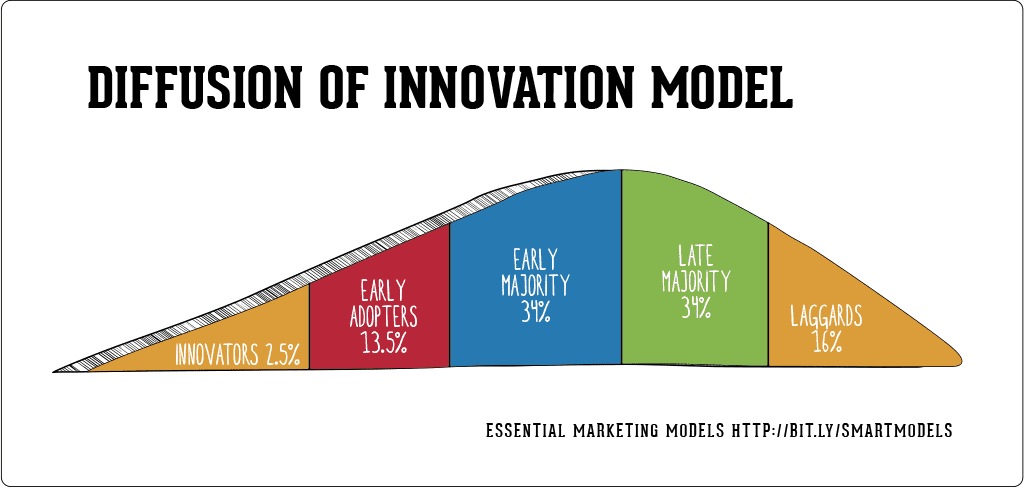

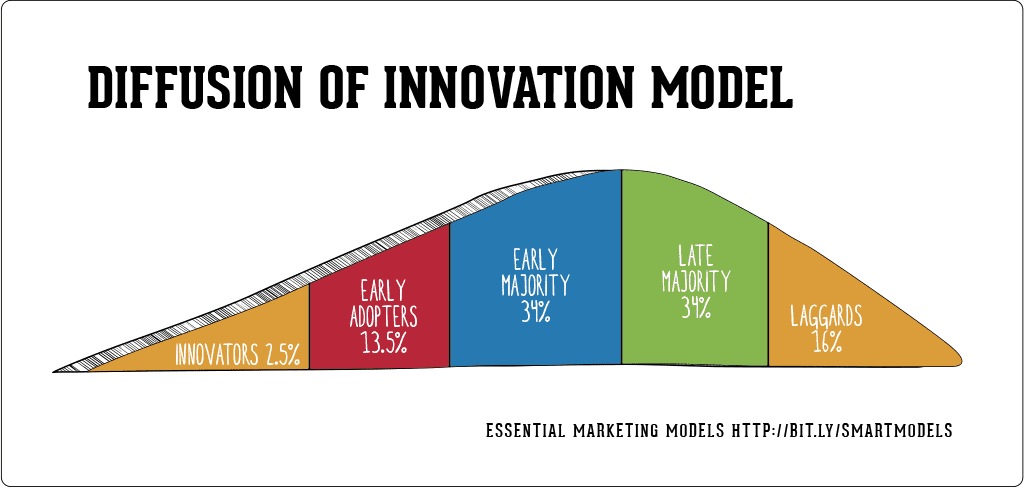

I think the diffusion of innovation model shows a fairly similar distribution between the willing and the motivated. I’ll argue that the innovators represent the motivated. They, in fact, don’t even need direction or support. Those early adopters represent the willing but perhaps need some support and direction to move forward with innovation. Those in the early and late majority need a lot of support, direction and perhaps even convincing. They’re waiting and watching the motivated to see if indeed things will work. When schools and districts refer to “pockets of innovation” they’re talking about the first two groups. They have teachers who are doing the right work in spite of the lack of support and those districts that have gotten somewhat intentional have found ways to support the early adopters. These are the easy folks to support. They don’t need much in terms of resources and money. But of course, most teachers and students lie on the right side of the graph.

This is really the greatest challenge we face. I think this is much more of a long-term grind and I’m not entirely sure how to get there. Engagement remains an important part of this process. Teachers sharing their passions and interests isn’t necessarily a bad thing and in fact, should be embedded into all student experiences. But digging deeper into what it takes to develop willing students and teachers is key. I think it’s a fairly complex question in part because it requires deeper relationships. Those relationships need to be founded on trust and the greatest challenge is building a culture of trust. A student may indeed develop a willingness to learn and take control of their learning with one teacher but unless their next teacher and experience allow them to continue that journey, they’re likely to revert. In the Thames Valley district, when teachers were given the opportunity to craft their own programs with no subjects and increased autonomy, one clear response was, “Don’t tease me”. In other words, these teachers, like millions of others had been burned by leaders who may have promised them an opportunity that sounded great but either was not what they thought it was or it didn’t last.

I’ve officially hit the rambling stage, fully aware I’m trying to take a very big issue in education and trying to make some sense of it. I suppose I’m simply asking these question:

Do you see a difference between willing and motivated?

What does it take to create and develop willing teachers and students?