I’ve had a few conversations lately with family, friends and colleagues about self-awareness. I find it fascinating as a personal introspective but wondering if it can be and should be explicitly taught. For the most part, I consider myself pretty self-aware. I suppose most people would say the same. We like to think we’re honest with ourselves about our strengths and weaknesses and foibles and annoyances. It usually takes more than simply being reflective to address this. It requires the eyes of others to at times let you know when you’ve missed the mark or even when you’ve done well but weren’t even aware of the impact. On more than one occasion, I’ve come to terms with my own lack of self-awareness.

Exhibit 1:

I’m one of the worst complimenters on the planet. This is now a running joke among the folks I work with at Discovery Education. I have a bad habit of using “actually” or some other odd qualifier when I give people a compliment. “Actually, that’s not a bad shot” (ask Steve Dembo for the full story) I certainly wasn’t aware I was doing this but after being called on it more than once, I now can catch myself when I do it.

Exhibit 2:

Sometimes I shut down. After doing one of those online tests, it would appear I’m an ambivert. Which means, that while I’m not bothered by crowds, I often suddenly reach capacity and then shut down. My wife will call me on it later and tells me it was rude. It was, but certainly I didn’t intend that to be the case. Now she warns me when she senses I’m done.

I could go on. but you get the idea. Golf is a great metaphor for this. When you swing the club, you don’t see what your playing partners or an instructor might see. You feel as if you’re doing one thing and they tell you you’re doing something very different. The advent of video has dramatically changed golf and other similar skill based activities as we now can see what previously we could only surmise from a narrow perspective.

I value the support of others in my learning. In fact, it’s another reminder that quality learning needs to be social and that reflection, assessment and conversation are integral to growth.

I recently received some peer reviews from the book I’m working on. There were 4 reviews. Three were mostly positive and certainly made me feel good. The 4th wasn’t very glowing. In fact, let me share with you some of the critiques:

I do not think that the coverage will appeal to the audience the way it is written. There are several places where the reader could stop reading the information due to being told this is not the book for them or if they have made it this far in the book they may have a different perception. Although the book is conversational and I find it useful to tell the reader what the book is and is not, do not turn the reader away or devalue important information.

The manuscript’s major weaknesses were inconsistencies within theconversational style of writing. There were parts that seemed extremely choppy when read and others that were long and detailed. There were also areas that seemed to focus on a topic covered in another chapter rather than focusing on the matter in the given chapter.

At this time, I do not recommend publication of this book. I think the ideas are valuable to education but need to be more concisely and fluently written. After this is done I think this book could start many valuable and honest conversations about joy between educators.

I didn’t like reading this. Like many people, the first reaction to criticism is to reject it and consider reasons why it was off base. Maybe enlist others to support you and collectively renounce the challenges.

But after reflecting, I knew this person was right. I have no dreams of being a great educational writer. I have no illusions of writing a best seller, but I do want to be proud of my work. Without the eyes of strangers and peers who can see things objectively, I don’t think I can achieve the level of success I’m seeking.

Self-awareness also means understanding that others will see you one way and you have to make a chose. As I write this I got a tweet from Katia Hildebrandt who teaches pre-service teachers.

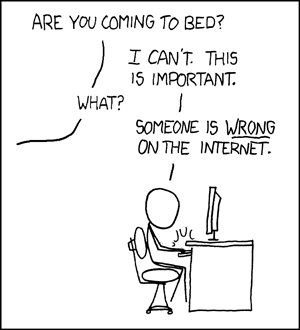

This is not the first time students have sleuthed me. I fully understand that they will often call me an “oversharer” and focus on the trivial, goofy things I share. I don’t argue that. I also am aware that I’ve likely lost followers, speaking engagements and other opportunities because of how I interact on twitter. This has remained for me a conscious decision to use social media to be social and personal first, professional second. I understand that the current mantra around branding would suggest I’m doing it wrong. That said, I’m grateful for various perspectives that challenge my thinking and by no means do I pretend to do things correctly. But I do ask people to think about the idea of self-awareness even in these online spaces.

Recently my daughter told me about Photo Feeler, an app that gives you unbiased feedback about your profile photo. If you’re looking to use one for a site like Linkedin, having the right kind of photo, matters. Kiwi is another app that allows you to get anonymous advice from friends. While I see lots of problems with these apps, the idea of actively seeking feedback is interesting.

Self-awareness might be one of the most underrated skills. It seems like a key disposition to success. Being intentional is a great first step. Having people, friends and strangers who can offer unique perspectives is the next step. Being able to process this and move forward completes the cycle.